Forty years of British Independent television celebrated in Amsterdam

by John Henshall

The author... as he might have looked on tv in 1955!

The kind of photography which television employs is - and always has been - electronic imaging. Without electronic imaging, television would still be called radio.

When the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II - the then biggest-ever outside broadcast - caused a huge explosion in television receiver purchase in 1953, there was still only one television channel: the BBC Television Service. It was transmitted in black and white, with 405 lines making up each picture. Apart from a short wartime break, television had been like that since it started in 1936. The receivers of the day were preset for the local transmitter and had no variable tuning. The Sunday Play was repeated midweek, again broadcast live. There was no videotape recording, no ITV, no television commercials.

All that changed suddenly in September 1955, when ITV blasted onto British television screens. TV sets sprouted extra boxes, with a rotary tuner for the new 'Band Three' - higher frequency, transmissions. 'Gibbs SR' toothpaste, in a block of 'ice', appeared in the first 'natural break' between programmes.

Independent Television had arrived.

No longer did the television audience belong exclusively to the BBC. Associated Rediffusion and ATV divided the viewers and doubled their choice. They were followed by ABC and Granada - cinema chains turned television companies - hedging their bets as cinema audiences began to stay at home for their evening entertainment.

To mark this significant anniversary, the National Museum of Photography Film and Television had a fully-working 1950s vintage television studio at the International Broadcasting Convention, Europe's premier showcase for broadcast television technology, held in Amsterdam in September 1995.

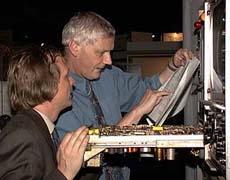

Paul Marshall and John Trenouth consult the original circuit diagram to correct a fault on one of the CCUs (camera control units). MTBF (mean time between faults) rose from 4 hours to 12 hours during the show - about what it would have been in a studio forty years ago.

From left to right, Marconi MkIII, Marconi MkIV and Pye MkIII cameras.

The exhibit brought a tear to the eyes of those who worked in television in the monochrome days of valves and large camera tubes. It was a haven of nostalgia and counterpoint - a place to escape from the digital world and reminisce about lost craft skills and the days when Britain actually made broadcast television cameras. The stand also enabled more youthful broadcasters put today's television into context by showing them what television was like in the days before colour, videotape, digital effects and post-production - when everything was either 'live' or on film.

Television Curator John Trenouth with Michael Cox, Chief Executive of the International Broadcasting Convention. Mike worked with these very Marconi MkIII cameras in his days at the Rediffusion studios in Wembley, north London.

Elsewhere at IBC, the latest digital technology stood out in sharp contrast, emphasising just how far television has developed. But will all the new

digital equipment still be working in forty years time?