KODAK DIGITAL CAMERAS

The KODAK DCS100 and DCS200

by John Henshall

Using the DCS100 and DCS200 at the first electronic imaging

Academy workshop, held at the EPIcentre on May 27th 1993 are Amy Quigley,

Paul Wenham-Clarke and Gianna Tognarelli.

Left: the original DCS100 with image pack and umbilical cord.

Right: the self-contained DCS200.

Photography needs more sex - sexy, desirable products

which capture the imagination and arouse a yearning to be possessed.

The Kodak DCS 200 is such a product. Sexy, because it is a state-of-the-art

product, packed with up-to-the-minute technology. Desirable because it is

compact, easy to use, and offers quite remarkable quality.

Desirability can cause temptation, and it was temptation which proved just

too much for the person who stole the DCS 200 from under my nose at a recent

conference in Edinburgh.

Yes, the DCS 200 really is a most desirable product

If anyone should come across a DCS 200 with the serial number K380-0015

on the baseplate, please let me know. This serial number, the thief may

be interested to learn, is also embedded in every image file the camera

records. The camera was fitted with an AF Zoom-Nikkor 35-70mm 2.8 lens,

serial number 263429.

The DCS 200 is the second in what is still a unique line of truly portable

'instantaneous' digital cameras from Kodak. Yes, there are other digital

cameras but, as yet, they are all tied to the studio and powerful computers.

The use of such cameras is also restricted to tripods and still life subjects

because of the long exposure times - up to half a minute - required for

the three sequential exposures through red, green and blue filters.

There are no other professional digital cameras quite like those from Kodak.

THE JAPANESE CATALYST

Was it the advent of the Sony Mavica, over twelve

years ago, which made Kodak realise that, one day in the distant future,

the whole of Kodak could be filmless? All manufacturers of conventional

photographic products must hope that this changeover will not come too soon,

for they are highly dependent upon their chemically-based core business,

which pays today's salaries and finances research into tomorrow's imaging.

A rapid changeover could prove dangerous, but any manufacturer who got into

filmless photography at the ground floor would remain a major supplier of

photographic equipment and materials. Thus the research started.

ENTER THE DCS

Despite this, it came as something of a surprise

to the photographic world when, in 1991, Kodak produced the first totally

portable Digital Camera System - the DCS, since renamed the DCS100.

Some reaction to the introduction to the DCS100 placed it in the realm of

the space age gismo, far removed from everyday photographic reality. Perhaps

it was a product launched ahead of its potential market, but for many people,

myself included, it heralded the real start of the digital revolution: imaging

the future.

Kodak realised that if they expected a photographer to get to grips with

a totally strange camera, they might attract a certain amount of prejudice.

Give a photographer something he is already at home with and you make him

feel secure. So the Kodak DCS uses a familiar unmodified Nikon F3 camera

body. Only the focusing screen and motor drive have been changed. All the

F3 camera functions are retained, and the DCS uses standard Nikon lenses.

Inside the back is a Charge Coupled Device or CCD, a light sensitive integrated

circuit which converts light into electrons. It has 1.3 megapixel resolution

in a 1024 x 1280 pixel array which measures 20.5 x 16.4mm, as against the

36 x 24mm standard for 35mm gauge film.

Here are a couple of easy rules for lenses. Multiply

by 1.8 to work out what equivalent focal length your existing lenses will

give on the DCS100. Divide by 1.8 the focal length you would use for 35mm

film, to arrive at the focal length of the lens you need for the DCS100.

Thus, the 'standard' lens would be a 28mm, giving a horizontal angle of

view roughly equivalent to a 50mm on an SLR.

The focusing screen is marked out to show the revised field of view, with

a cross-hatched surround through which can be seen the image which would

be obtained if using 35mm film. The disadvantage is that this gives a small

picture in the middle of the viewfinder, but the advantage is that it gives

a useful pre-warning of things just about to enter frame, without having

to take the eye away from the viewfinder. All Nikon exposure controls work

as normal.

The relative speed of the camera back is ISO100.

The exposure can be 'pushed' by one, two or three stops to ISO200, 400 or

800 on an individual shot-by-shot basis. You do not have to expose a whole

'roll of film' at the same ISO rating with electronic cameras.

The DCS 100 has to be connected to its Digital Storage Unit, 'DSU', by an

umbilical cable. The DSU is a battery operated 200 megabyte recorder which

can store about 150 uncompressed or 600 compressed images. Motor-driven

exposure bursts can be made at a rate of 2.5 per second, in from six to

twenty four image bursts, depending on how much RAM (Random Access Memory)

the DSU has on board. The DCS 100 is thus ideal for instant filmless photo-journalism.

The DSU allows full control of the recorded images, from viewing the exposure

on the built-in monochrome LCD (Liquid Crystal Display), to deleting unwanted

images to make room for further exposures.

My first picture on the DCS was a shot across the small dam behind Kodak's

Center for Creative Imaging, in Maine, in July 1991 on the prototype - serial

number 001. The camera felt familiar to me immediately, as a long-time user

of the Nikon F3.

The small LCD monitor screen on the DSU gives true instant pictures, from

which the exposure and composition can be assessed in the field. Back at

base, you can look through the exposures immediately in black and white

on a large-screen television monitor, without any delay for processing.

Then, only the chosen shots are imported into a computer from the DSU. The

remainder are deleted direct from the DSU.

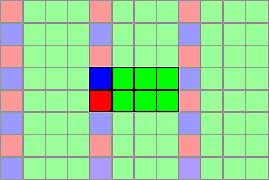

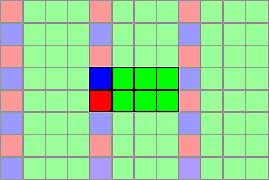

The pixels of the DCS 100 are coloured in a special way. Three out of four

vertical rows of pixels are coloured green, amounting to 75% of the total.

The fourth vertical row is alternately red and blue, each amounting to only

12.5% of the total.

The DCS100 pixel array.

The files on the DSU are only one third the size

of files imported into the computer. When the 'raw' electronic image is

imported, the software compares the signals from adjacent pixels and uses

them to interpolate and reproduce colours correctly. This clever technique

works better on some subjects than others. Although it works well on faces,

and other round and textured surfaces, it does not work quite so well on

linear subjects, such as white window frames, which run almost parallel

to the vertical stripes of the CCD. These often display colour aliasing

- 'jaggies' - caused by the software making incorrect colour decisions.

The aspect ratio of the DCS 100 is 1:1.25, the same as 4 x 5 and 8 x 10

inch film and prints.

The system costs around £15,000. A black and white version is also

available.

DCS 200

To many people's amazement, in August 1992 Kodak

launched a second digital camera - the DCS 200. This camera is not a replacement

for the DCS100, but rather complements it.

First and foremost, the camera is completely self-contained. No umbilical

cable. Again it is based on a Nikon body - this time the autofocus N8008s,

or 801s as it is known in Great Britain. The CCD ratio has been changed

from 1:1.25 to 1:1.5, the same aspect ratio as the standard 35mm film frame.

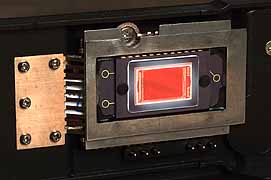

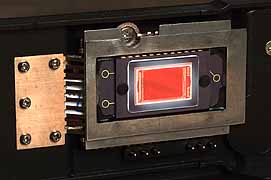

The new 1.54 megapixel chip has more pixels, but is physically smaller than

that in the DCS100. The chip has 1524 x 1012 pixels in a 14 x 9.3mm array.

The DCS200 CCD.

Lenses therefore react differently on the DCS200, but the 'conversion'

rules are again very simple. Multiply by 2.5 to work out what equivalent

focal length your existing lenses will give on the DCS200. Divide by 2.5

the focal length you would use for 35mm film, to arrive at the focal length

of the lens you need for the DCS200. Thus, the 'standard' lens would be

a 20mm, giving a horizontal angle of view roughly equivalent to a 50mm on

an SLR. The DCS200 is supplied with a 28mm 2.8 AF-Nikkor, equivalent to

a 70mm focal length with 35mm film.

The DCS200 viewfinder.

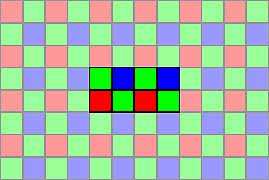

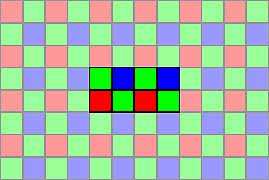

The new chip uses a similar system of interpolation of adjacent colours

to that in the DCS100, but the technique has been much improved by new filtration

of the CCD elements. On this chip red, green or blue elements are never

more than one pixel away - on the DCS 100 they could be twice as far away.

This greatly reduces colour aliasing and increases resolution.

The DCS200 pixel array.

The reduction in the number of green pixels brings about a lower sensitivity

of ISO50 for the DCS200, which may be 'pushed' to ISO100, 200 or 400. Both

DCSs behave like reversal film. Exposure is quite critical because, once

over-exposed, the highlights are gone forever - just like clear emulsion.

Under-exposure is not so much of a problem, for, to some extent, exposures

can be "intensified" electronically.

Unlike the DCS100, the DCS200 can only take one image every three seconds

- this is as much as can be stored in the 2Mb of on-board RAM and the time

it takes to 'save' that image to the hard disk. The camera has a built-in

80 megabyte hard disk which will hold fifty images. When the fifty exposures

have been made, that's it - until the images have either been downloaded

to, or deleted by, a host computer. In an emergency, the last image recorded

can be deleted by pressing a ball point pen into a special hole in the camera

back, allowing a further exposure to be made. The only other way to record

more than fifty images is by using a small battery portable hard disk, the

Mass Microsystems' Hitch Hiker, strapped to the back of the camera. Unlike

the DCS 100, it is not possible to view the DCS 200's images without a computer.

Left: The DCS200, rear view. Right: The upper LCD shows disk

usage and battery power, the lower panel the ISO and status reminders.

All this technology runs off just six re-chargeable

AA-size ni-cads, plus four AA size alkaline cells to power the Nikon body.

The Sanyo N-600AA Cadnica cells supplied with the camera are rated at 600mAh

each, higher capacity than normal rechargeable AAs, which have a 500mAh

rating. However, Ever Ready RX6 High Capacity cells are now available with

a capacity of 650mAh. These should give longer shoot times between charges.

For best results, all rechargeable batteries need careful treatment and

should be discharged fully before receiving a slow recharge. Don't leave

them on the charger or you will 'cook' them.

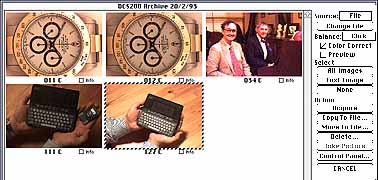

Both cameras allow the archiving of 'raw' files on a host computer, for

later processing as full colour images. These archive files may be browsed

using the Kodak software (supplied for both Mac and PCs) which produces

thumb-nail reference images or a larger preview image. At this stage, colour

balance can still be changed on a shot-by-shot basis, with pre-set compensation

for daylight, flash, fluorescent, tungsten and 'click'. This last option

allows the selection of a white or grey element in a shot which may be 'clicked'

on to neutralise the colour balance. I include a grey card in a spare exposure

and find this a particularly useful facility. From this, a whole session

may be colour balanced, even if it was shot under mixed lighting. The facility

may be compared with that of 'white balancing' video cameras. I have also

found an overcast sky to be a suitable component of the picture on which

to colour balance.

The DCS200 Photoshop plug-in for Macintosh

"BUT ISN'T IT REALLY A NIKON?"

The cameras are frequently referred to as 'the digital

Nikons', and it is true to say that a considerable amount of misunderstanding

surrounds the Kodak Digital Camera Systems. This is perhaps understandable

for Kodak have not been known as professional camera manufacturers for some

years and both cameras retain the Nikon name on their pentaprism housings.

But, no! Both are Kodak cameras. For convenience and familiarity they use

existing Nikon bodies and lenses. Why re-invent that wheel?

Then there is photographic snobbery and prejudice. A magazine which recently

'tested' digital cameras did not include the DCS200 in its tests "because

it is 35mm and none of our photographers would be seen dead using 35mm."

What crass, ill informed prejudice! They did not even stop to consider that

the CCDs inside the Kodak DCSs are not only larger but have many more pixels

than the CCD inside one of the view cameras they tested.

Maybe I should consider mounting the CCD from a Logitech FotoMan on the

back of an 8x10 inch Sinar? "Of course, darlings, we use the 8x10 Sinar

digital back. In our [posey] position we couldn't possibly be seen using

anything smaller." Like so many other things in photography, such attitudes

will have to change.

Below: John's DCS200 shot of the Last Supper

stained glass

in Durham Cathedral

(photo permit paid) has been

archi-

tecturally corrected by applying

a 'rising front' electronically.

The DCS200 is supplied in five versions:

I have majored on the DCS200ci here, 'ci' standing for 'colour' and 'internal'

hard disk. The colour version is also available as the DCS200c, without

internal hard disk storage, for use only while linked to a host computer.

Similarly, there are black and white versions with and without internal

disks: the DCS200mi and DCS200m. There is also a 'hybrid' colour version,

the 'Wheelcam', which uses the black and white chip and makes a triple exposure

through red, green and blue filters in turn, in a manner similar to the

Leaf digital camera. The price of the DCS200ci is about £7000 - less

than half that of the DCS100.

The DCS200 is supplied in five versions:

I have majored on the DCS200ci here, 'ci' standing for 'colour' and 'internal'

hard disk. The colour version is also available as the DCS200c, without

internal hard disk storage, for use only while linked to a host computer.

Similarly, there are black and white versions with and without internal

disks: the DCS200mi and DCS200m. There is also a 'hybrid' colour version,

the 'Wheelcam', which uses the black and white chip and makes a triple exposure

through red, green and blue filters in turn, in a manner similar to the

Leaf digital camera. The price of the DCS200ci is about £7000 - less

than half that of the DCS100.

Both Kodak digital cameras have SCSI interfaces, which means that they can

be connected to any Apple Macintosh computer very easily. PCs need a SCSI

(Small Computer Serial Interface) card. All the necessary cables are supplied

with the camera.

I have now been using both the DCS100 and the DCS200 for some months for

all my editorial and product photography for this column. For this work,

they are ideal. Indeed, it would now be inconvenient for me to go back to

using film.

The DCS image has the same aspect ratio as a 35mm full frame, but a standard 50mm lens equals a 125mm telephoto.

I make no apology for my genuine enthusiasm for these fine professional

products, the most inspiring pointers so far to the revolution which is

upon us.

What of the future? Even more pixels? Removable hard disks? Faster 'motor'

drives? Maybe. What is certain is that these Kodak digital cameras are the

future of imaging. And they are here, right now.

This review first appeared as "John Henshall's Chip

Shop" in "The Photographer" magazine, June, 1993.

IMPORTANT NOTICE

This document is Copyright © 1996 John Henshall. All rights reserved.

This material may only be downloaded for personal non-commercial use. Please

safeguard the future of online publishing by respecting this copyright and

the rights of all other authors of material on the Internet.

The DCS200 is supplied in five versions:

I have majored on the DCS200ci here, 'ci' standing for 'colour' and 'internal'

hard disk. The colour version is also available as the DCS200c, without

internal hard disk storage, for use only while linked to a host computer.

Similarly, there are black and white versions with and without internal

disks: the DCS200mi and DCS200m. There is also a 'hybrid' colour version,

the 'Wheelcam', which uses the black and white chip and makes a triple exposure

through red, green and blue filters in turn, in a manner similar to the

Leaf digital camera. The price of the DCS200ci is about £7000 - less

than half that of the DCS100.

The DCS200 is supplied in five versions:

I have majored on the DCS200ci here, 'ci' standing for 'colour' and 'internal'

hard disk. The colour version is also available as the DCS200c, without

internal hard disk storage, for use only while linked to a host computer.

Similarly, there are black and white versions with and without internal

disks: the DCS200mi and DCS200m. There is also a 'hybrid' colour version,

the 'Wheelcam', which uses the black and white chip and makes a triple exposure

through red, green and blue filters in turn, in a manner similar to the

Leaf digital camera. The price of the DCS200ci is about £7000 - less

than half that of the DCS100.