The UK's Leading Authority on Digital Imaging

The UK's Leading Authority on Digital Imaging

Megapixel digital cameras are flooding onto the market this year. There's no doubt that they are a major improvement over last year's VGA resolution (640 x 480 pixel) one third of a million pixel cameras - last year's state-of-the-art products on which we are now encouraged to look down with disdain. Give it another year and we'll be looking back at today's one megapixel cameras in the same way.

That's progress - all part of the inevitable hype associated with the development curve of new products. Compared to their film counterparts, most digital cameras are down below the box camera end of the photographic scale in quality terms whilst up near the single lens reflexes in price. Yet most of them have fewer features than a compact and, unless you have a specific low quality use for them, they don't represent a good buy.

Megapixel cameras are in no man's land: better than required for images for the web but still not good enough for a 10 x 8 inch print of photographic quality. Even at the low resolution of 200 pixels per inch, a 10 x 8 needs 3.2 megapixels. At this resolution, today's megapixel cameras would only be good enough for a 6 x 4 en-print. But image quality is not just about pixel count: image processing is another factor which can drag quality down.

When it comes to scanners to digitise the old plastic stuff, we're already able to analyse all the detail of a 35mm film frame into 6 million pixels or more. This comes for only a few hundred pounds, making film a great digital image mastering medium - if you can bear the wait for processing.

Most things in digital imaging are judged by the yardstick of 'photo quality' and when it comes to printers, we're there. The Epson Stylus Photo EX will print 11 x 44 inch prints and costs less than £400. That's a lot cheaper than a wet darkroom full of gear.

Problem is, all these products are still linked together by a computer and loads of spaghetti. (Remember the John Cleese Sony commercial?) It's this, and slow download times, which makes digital imaging a lot more complex than dropping a film into Boots and passing a pleasant hour in the pub waiting for the results. It can easily take an hour to upload pictures from a digital camera. It's labour intensive and the novelty soon wears off - though we do retain complete control over our images.

What we need are cameras which allow us to sit in our armchairs and preview images on our television sets without any cable connection at all, using an infra red link. After setting the crop and number of prints required for each shot, we sit back and watch the match while the printer, built into the VHS recorder, churns out the prints. People still like real prints, which they can handle and enjoy anywhere without special viewing equipment.

Alternatively the whole print system could be built into the camera - the digital version of that original instant imaging system, the Polaroid. Polaroid probably already have a prototype secreted away in their Cambridge, Massachusetts, headquarters - though it's likely to be a bit on the bulky side at the moment.

They've

just launched the ColorShot printer, only slightly bigger than a Zip

drive, which may give us some pointers. It uses LEDs to expose

standard Polaroid 'instant' film. Street price is expected to be

under £200. Put a lens and CCD on one end, an LCD panel on top

and removable media underneath and you have… a self-contained

digital Polaroid.

They've

just launched the ColorShot printer, only slightly bigger than a Zip

drive, which may give us some pointers. It uses LEDs to expose

standard Polaroid 'instant' film. Street price is expected to be

under £200. Put a lens and CCD on one end, an LCD panel on top

and removable media underneath and you have… a self-contained

digital Polaroid.

The problem with Polaroids has always been that you can't make multiple prints, or reprints, of the same shot of live subjects. On-board storage media would allow the reprinting of identical shots; removable media allows images to be archived or transferred into the computer, for use in of all kinds of documents.

Film and television makeup artists need instant reference shots at each stage of their complex special effects makeups, so they remain big users of Polaroid. A hybrid camera, offering both 'instant' prints and the ability to archive digital shots for later use and incorporation into other documents, would give them what they want now plus some useful new features.

While Polaroid - or perhaps another major photographic supplier - are working on that idea, we have to make the most of today's low resolution digital cameras.

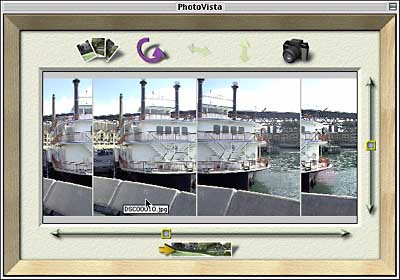

Joining images together can make a number of small files into one large file. There are a number of techniques. I used a Fuji DS300 on its 640 x 480 pixel setting to capture twenty four images of Sydney harbour, then used Live Picture's PhotoVista software to assemble them as a panorama.

PhotoVista took only forty six seconds to look for similar points in each of the overlapping images and join them, end to end. Enroute uses similar techniques to tile images in two directions, as a mosaic. Taking the technique to its extreme, I assembled over a hundred images captured from a digital video camera at a wedding into a huge collage. The resulting 100MB file produces superb 20 x 30 inch prints of incredible detail and interest.

Don't be restricted by today's technology. All you need is a little ingenuity to make low resolution images work for you in new ways.

IMPORTANT

NOTICE

This document is Copyright © 1998 John Henshall. All rights

reserved.

This material may only be downloaded for personal non-commercial use.

Please safeguard the future of online publishing by respecting this

copyright and the rights of all other authors of material on the

Internet.